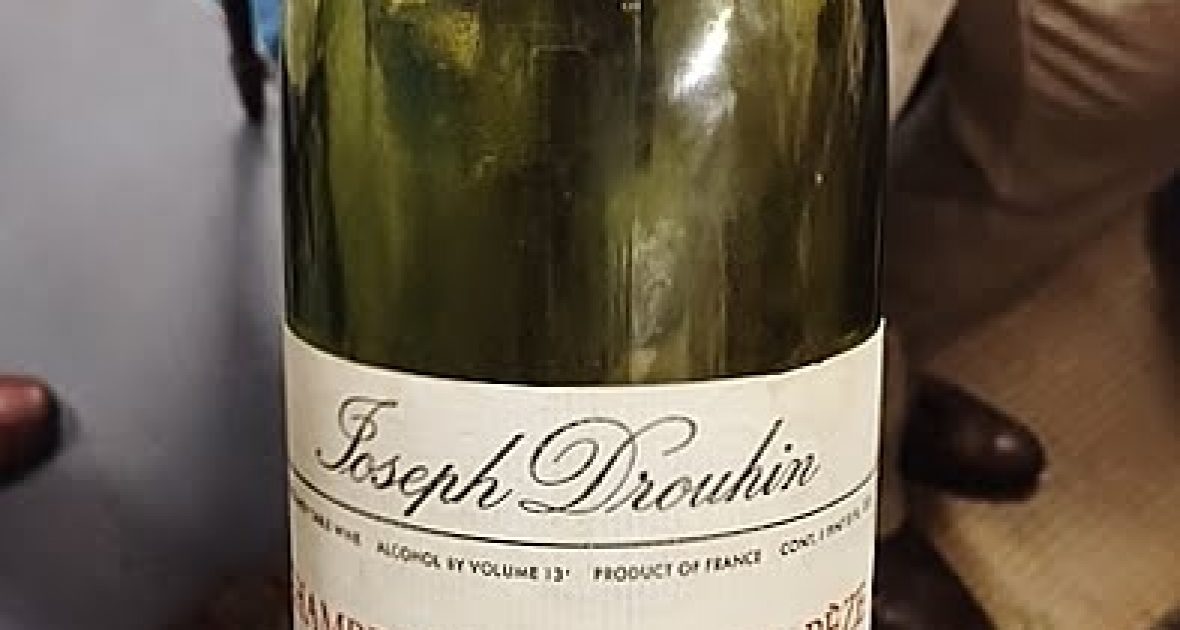

The beginning of the end was, for me, Joseph Drouhin’s Clos de Bèze 1973.

This bottle completely changed my relationship with Pinot noir—that maddening yet beautiful wine that I’ve come to love more than any other, but which has also disappointed more often than not.

I knew I liked Pinot noir before this bottle. I had no qualms with it whatsoever. It was easy drinking and friendly. But the 1973 Clos de Bèze showed me a side of Pinot—no, of wine—that I never knew existed. It brought me through twenty different aromas and tastes, and three minutes after I had swallowed my sip it was still lingering on my tongue. That wine marked the end of my search for truly great Pinot—but it also marked the beginning of a frivolous journey to seek out that experience again. Stupid.

Pinot noir is known as “the heartbreak grape,” and they don’t call it that for nothing. But you don’t realize that the concept of heartbreak even exists unless you also know about true love. And once you get a taste of true love, most everything else pales in comparison—at its best it’s blasé; at its worst, it’s horrific. This all sounds ridiculously over romanticized and it most certainly is, but I’m telling you—I have never tasted anything that has come even remotely close to the glory of that 42 year old Pinot noir.

42 years old! And this wasn’t a hardy, tannic, tough-guy Cabernet or even a stalwart Barolo. This was a delicate, soft, shy little wine that was as light as a feather. How on earth could a wine so fragile outlast so many others with more power, more guts, and more potential?

It’s high time we took a close look at Pinot noir, the most maddening grape in the world.

Did you know that there’s an entire field of science dedicated to unraveling the genetic history of grapes? There are people out there who make it their life’s work to map out the DNA sequences and ancestral charts of every known wine grape. Sounds daunting, right? They’ve only recently started doing this and they’ve got light years ahead of them before it’s completed, not to mention the fact that some grape varieties have gone extinct long ago and therefore have left major holes in the pedigree diagrams. But they’ve already made some fascinating discoveries and it’s mind-blowing to see it all mapped out in one big ol’ family tree.

Older than the Hills

Remember how Cabernet Sauvignon came about? We discovered that it was a pretty young grape in terms of how long it’s been around. Pinot, on the other hand, is absolutely ancient. In fact, some of the most reliable resources we have for grape genetics put it at the very top of the map. There are currently over a thousand registered clones listing Pinot as one of the parents! Now, this could simply mean that Pinot just mutates easily, but in all reality, it had over 2000 years to propagate new little Pinotlings. Any reproductive species living that long would have a pretty hefty progeny too! Some of the most well known (and perhaps most surprising) offspring include Chardonnay, Gamay, Melon de Bourgogne (used in Muscadet in the Loire Valley), Aligote and Auxerrois. And if you look back even further, there’s evidence for Pinot being the grandfather of Syrah… and possibly even the great-grandfather of Cabernet Sauvignon!

Fickle, Finicky, and Fervid

How Pinot survived two millennia and is still today one of the most popular grapes for making wine is one of nature’s great mysteries—especially when you understand how difficult it is to grow this stubborn grape well. Pinot buds and ripens early, which gives winemakers awful headaches when they have to protect the vines from early frosts and decide when to harvest. It’s susceptible to scads of diseases, viruses, and pests. It’s pretty picky about what kind of soil and climate it will do well in; unlike its hardier children, it can’t grow just anywhere. But when the stars align and everything falls into place, Pinot can produce incredibly unique, exquisite, characterful wines. It picks up on every nuance of where it’s grown, including the soil, aspect and slope of the hill, and the weather of each individual vintage year, as well as any kind of manipulation from the winemaker.

The French call this hard-to-define concept “terroir”. The Cistercian monks living in Burgundy in the 12th century realized this pretty early on, and were the first to map out detailed growing areas based on how Pinot tasted in each plot of land. Burgundy is a complex checkerboard of soil types and microclimates. Knowing this, the monks held the land and vines in the highest regard. The special nature of the wines these grapes produced led them to view tending their vines as an act of prayer and reverence to God.

Because Pinot loves to mirror the place it comes from, we’ll explore three different expressions of it in order to get the full scale of its potential. Pack your bags for California, Oregon, and Burgundy!