Come together over glou-glou.

Continue readingA Visual Guide to Thanksgiving Wines

Most things in life are TL;DR. Quit wasting time and just look at the pretty pictures.

Continue readingA Love Letter To–and From–California

What happened, who’s hurting, and what you can do (it’s tastier than you think!)

Continue readingNo White After Labor Day? We Beg To Differ.

“It’s my party and I’ll drink white if I want to.” –Lesley Gore’s original lyrics

Continue readingY. Rousseau: Napa’s Little Gascony

Gascony comes to California!

Continue readingThe Oldest New World Country: Two Winemakers Who Are Changing the State of South African Wine

For being a country that has been producing wine for over three and a half centuries, it’s taken South Africa a while to shake off the “novelty” status the wine world has placed on it. But it’s time to start seeing it for what it has now become: a solid cornerstone in New World wine. South Africa has all the fixings of an ideal winegrowing region: a moderate climate with cooling influences from both the ocean and mountains, a multitude of various soil types, a range of elevations, and most importantly, a new generation of zealot winemakers who are fiercely committed to producing wines of quality, longevity, and character.

But while South Africa has always been endowed with prime natural grape-growing conditions, humans, it seems, needed a few centuries of winemaking trial, failure, and experimentation in order to get up to speed. Early on, the dry table wines of South Africa were less than impressive. But the early 18th century brought a new phenomenon to the French and English courts: the ultra-sweet, syrupy, unctuous, and extremely long-lived Vin de Constance. Alas, disease, mold, and foreign pests (looking at you, phylloxera) choked out any international fame South Africa’s wine scene had garnered, and things went downhill fast… for the next half century or so. Ginormous cooperative wineries appeared, hoping to normalize the industry, but it wasn’t until after the end of Apartheid in 1994 that things really got up and running again.

This is the history that Jasper Raats (of Longridge) and Lourens van der Westhuizen (of Arendsig) were born out of. Their world, though, has few ties to the tumult of past winemaking generations. They are part of an era of winemakers who have had the opportunity to travel, learn from other winemakers, and be exposed to horizons that their predecessors never knew about.

Jasper Raats is a wealth of knowledge when it comes to wine. Having held winemaking positions in New Zealand, California, Burgundy, and the Loire Valley, it’s safe to say he has some good experience tucked under his belt. All these ventures have led him to an extremely simplistic, pared-down, honest approach to how he makes his wines today at Longridge: no herbicides or pesticides, no commercial yeasts, enzymes or fining agents, and very minimal SO2 additions and filtration. In other words, he just stands back and lets the grapes do all the work. As we have seen time and time again, if you do the work right in the vineyard, there’s not much to do in the winery. His approach sings of purity, balance, and sustainability for generations to come.

Lourens van der Westhuizen of Arendsig Wines grew up amongst his father’s vines in Robertson, South Africa. Robertson is a place you have to want to go to: it’s over an hour’s drive inland from Cape Town, and not a pastoral wine hamlet you can accidentally stumble upon. Robertson has its big players, of course—Springfield, De Wetshof and Graham Beck, for example—but what makes Arendsig unique has been the shift in culture that Lourens has brought about from the time his father gave him a rocky, decrepit patch of virgin soil to experiment with. His goal was to make single-vineyard wines, showcasing the unique terroir and character that Lourens knew was there. “So often we want to rave about climate,” he says, “but it all starts with the soil.”

This weekend, you’ll get a chance to meet Jasper, along with Colyn Truter, brand manager for the tiny, artisanal Arendsig Winery. Not only are these guys passionate about what’s going on in South Africa; they’re also passionate about telling the world about their incredible wines. They’ll be pouring through a selection of their wines, all of which were hand-selected by our very own wine nerd Dustin Harkins during his trip to South Africa last January.

This is a tasting you won’t want to miss! Make sure to carve out a few minutes of your weekend to experience firsthand the exciting things going on at Longridge and Arendsig.

The “No Fear” Italian Wine Guide: Barolo

What to Expect

Italy, apparently, loves “B” names: Barbera, Brunello, Barbaresco… and Barolo, one of the most famous and beloved wines in all of Italy. The Barolos of today are powerful, burly red wines packed with flavor and structure, and command premium prices across the board—even the entry-level ones. But while a great Barolo can draw impressive murmurs from your dinner party, it’s not necessarily what we seek out for everyday occasions. Read on as we break Barolo down piece by piece to understand why it’s priced the way it is, when and how to enjoy it, and the ongoing afflictions between generations in this tiny part of the wine world.

The Nuts and Bolts of Barolo

Barolo is a village located in the region of Piedmont in northwest Italy, and only grapes grown within the boundaries of Barolo can be used in Barolo wine. Barolo will always be made from 100% Nebbiolo grapes—a dark, thin-skinned red grape that packs a punch with its high natural tannins, acidity, and alcohol. Because of these important components, Nebbiolo can be pushed in a lot of different directions; and like Pinot Noir, it takes on the character of the vintage and the place it’s grown very easily. Barolo will appear in your glass as light-colored and delicate, but don’t be fooled: one sip of a young Barolo will leave you peeling your lips off your gums! Although many consumers prefer to drink Barolo in their youth and at the height of their power and muscle, these grippy tannins will subside with cellaring over years or even decades. Well-aged Barolo will take on beautifully developed aromas of forest floor, dried rose petals, and a softly musky scent that makes many aficionados go weak at the knees.

Hill Country

The region of Barolo is full of gently rolling hills that vary in elevation, aspect to the sun, and soil type—all factors that contribute to how the Nebbiolo of each microclimate ripens and develops. Because of this, many winemakers choose to blend lots of Nebbiolo from different sites in order to gain a more complete expression of Barolo rather than just one single vineyard. Nebbiolo is usually grown higher up on slopes, while Dolcetto and Barbera are planted further down.

Hurry Up & Wait

According to Italian law, Barolo has to be aged 38 months before it’s released to market—and 18 of those months have to be spent in barrels. All that barrel time further contributes to the wine’s tannic structure, but it also gives the wine extra stuffing to last far beyond most other wines—sometimes by many decades. For this reason, Barolo has come to be known as one of the world’s great “cellar wines” that you can set away to mark special anniversaries or occasions.

Barolo’s Battlegrounds

Like any other part of the wine world, Barolo has gone through many growing pains in the last decade or so. The “traditionalist” approach—the way Barolo was made a few generations ago—employs a long, slow vinification, followed by an elongated time in huge, ancient casks. These wines would normally be ready to drink about a decade or more after they entered the market—definitely a waiting man’s game! The younger generations have sought after other methods, including a shorter maceration time, the use of smaller and newer barrels (called barriques), and a fruitier, softer style of Nebbiolo. And of course, there are producers who are solidly on the fence between these two battling sides. There’s no “winning” side in this battle—as famed wine writer Hugh Johnson puts it, “No one is right, and only those who decide to ignore the unique qualities of this grape and this place would be wrong.”

Perfect Pairings

Because of Barolo’s big tannins, it loves fat-rich foods like beef tenderloin, braised duck, ragu, or prosciutto. You could also pair it along dishes smothered in a béchamel sauce, creamy cheeses, or any number of hearty veggie dishes if you want to accentuate Nebbiolo’s herbal, earthy side.

Fail-Proof Pairing: The Meat Shop is featuring gorgeously rich New York Strip Steaks this weekend. The thick, fatty cap on this cut of beef makes the tannins of the G D Vajra “Albe” Barolo melt in your mouth!

The Classics

G D Vajra “Albe” Barolo, $42.99

Vajra’s “Albe” is a perfect introduction to Barolo because it employs younger vines and the mínimum amount of barrel aging in order to give a fruitier, softer side of Barolo that is meant to be enjoyed in its youth rather than a decade down the road.

Francesco Rinaldi Cannubi Barolo, $69.99

“Cannubi” is one of Barolo’s 11 communes, and thus this bottling by Francesco Rinaldi can be considered a “single vineyard” Barolo. Sweet, yet firm, tannins wrap around a core of ripe red cherry, mint, pine, cedar, tobacco, and white pepper. This Barolo is meant for the long haul, but can also be enjoyed now.

Something Different

Nino Negri “Quadrio” Valtellina, $19.99: Barolo isn’t the only place Nebbiolo is grown! Valtellina is nestled far up north in Lombardy (just east of Piedmont), in the foothills of the Alps. This “mountain Nebbiolo” is considerably lighter-bodied than Barolo, but with no less aromatics and character. Soft, open and silky, this wine has notes of crushed flowers, tobacco and red stone fruits that are laced together nicely with a bright core of acidity.

Vietti “Perbacco” Langhe Nebbiolo, $28.99: This gorgeous Nebbiolo comes from vineyards outside of the Barolo confines, so therefore doesn’t have the Barolo price tag either. Coming from vines with an average of 35 years old, it is aged for 4 months in barriques (small barrels) followed by another 20 months in big casks. Generous fruit melds with menthol and spices, and the palate is at once powerful and elegant. This is a perfect bottle for those who want a version of a “baby Barolo”!

Vajra Barolo Bricco delle Viole 2003, $59.99: There aren’t many bottles with greater value in the store right now than this 2003 single-vineyard Barolo from G D Vajra. The experience this aged wine will give you far outweighs the shelf price; for those who want to see what a well-aged Barolo can provide, this is the bottle you need to take home. Bricco delle Viole is located on the western border of Barolo, and gives the wine an extraordinary clarity and precision of fruit, superb depth, and a stunning overall balance.

The “No Fear” Italian Wine Guide: Prosecco

WHAT TO EXPECT

Prosecco is, without question, the world’s favorite sparkling wine. Outselling Champagne and Cava combined in recent years, Prosecco has become the standard for “sparkling wine” in restaurants and households worldwide. It’s grown so popular, in fact, that in recent years (particularly 2015) there have been fears of shortages in being able to keep up with the demand. (The horror!) But what exactly is Prosecco, and what makes it different from any other sparkling wine?

First, here’s a little vocabulary lesson that applies not only to Prosecco, but to a lot of other sparkling wines made around the world as well:

- Spumante: Italian for “sparkling wine” with full-on carbonation; all Prosecco is spumante

- Frizzante: meaning “crisp” or “fizzy” in Italian; term for a slightly carbonated wine that is more effervescent rather than sparkling; Moscato d’Asti is an example of frizzante

- Extra Dry: technically an “off-dry” style, most Prosecco is Extra Dry. Between 12-17 grams of sugar per liter; fruity with perhaps a touch of sweetness

- Brut: a sparkling wine with no more than 12 grams of sugar per liter; no discernable sweetness

- Cuve close: bulk-production process for sparkling wine, in which the base wine is combined with sugar and yeast in a big tank to undergo secondary fermentation and then bottled; perfect for retaining the fresh, fruity quality of sparkling wines made in this method

- Method Champenoise: process for sparkling wine that must be used in Franciacorta, Champagne, and a few other high-end sparkling wines

Because Prosecco is made using the cuve close method, it will hardly ever be expensive. Only a few premium labels will command higher prices, with most of these coming from a tongue-twisting village called Valdobbiadene, located in the rolling hills just north of Venice. These wines have a more serious tone to them, with more refined flavors and aromas.

You can expect crisp, ripe flavors of apple, pear, and gentle citrus notes in Prosecco. The bubbles are big and lively, and because most Prosecco is Extra Dry (a confusing term for something very slightly sweet), it’s an easy sparkler to love—and to put in Mimosas.

- Did you know? If the label says “Prosecco,” it’s made with grapes of the same name—Prosecco! But Prosecco grapes also have another name: Glera. It’s extremely rare, but it’s possible to find still Glera without carbonation.

Perfect Pairings: The youthful fruitiness of Prosecco is a perfect foil for the saltiness of prosciutto. (If you need a killer party-starter, pour Prosecco next to some prosciutto-wrapped melon. Molto bene!) Prosecco is also a great match for frutti di mare, spicy Asian entrées, or even simple snacks like potato chips or buttered popcorn.

Fail-Proof Pairing: Our Cheese Shop has a little in-house creation that’s absolutely to die for: Signature Chevre. Creamy goat cheese medallions are topped with a signature blend of dried fruits, nuts, herbs, and olive oil that absolutely melts in your mouth. The sweetness of the fruit and tanginess of the chevre is an absolutely perfect pairing with the Nino Franco Prosecco Valdobbiadene Brut

THE CLASSICS

Mionetto Prosecco Brut, $14.99

Nino Franco Prosecco Valdobbiadene Brut, $21.99

SOMETHING DIFFERENT

Zardetto Spumante Rose, $13.99: This delightful spumante is made not from Prosecco grapes but from Raboso Veronese, which gives the wine its lovely soft-pink color as well as its vibrant acidity. Elegant and expressive, it has fresh aromas of cherry and red currant with a crisp, refreshing finish. Best paired to Parmigiano Reggiano and salame!

Lini Labrusca Rose Lambrusco, $19.99: Coming from the plains of Emilia between Parma and Bologna, Lambrusco is made in the same fashion as Prosecco—except with red grapes! This gorgeous rose Lambrusco is made from two strains of Lambrusco grapes—Salamino and Sorbara—and after a very short time on the skins, the juice is drawn off and then goes through secondary fermentation. It has intense aromas of ripe cherry and rose petals, followed by a crisp, fresh palate with nicely balanced acidity. Pair with antipasti, seafood, cheeses, and light pasta dishes.

Ronco Calino Franciacorta, $33.99: Franciacorta separates itself from any other sparkling Italian with one clear distinction: by law, it must be made in the same fashion as French Champagne—that is, the secondary fermentation (how it gets its bubbles) happens inside each individual bottle instead of in a large tank. This method, called methode champenoise, is costlier and more time-consuming, but ultimately higher quality. This Ronco Calino Franciacorta, made from 100% Chardonnay, is a prime example with its fine strands of bubbles (much smaller than in Prosecco), more delicate and nuanced aromas and flavors, and longer finish. Expect a bouquet of white lilac, acacia and orange blossom on the nose, followed by a palate full of pineapple, pear, and white cherry, as well as hints of honey, lime, and sage.

The “No Fear” Italian Wine Guide: Pinot Grigio

Pinot Grigio is just like your favorite old sweatshirt: it’s not flashy or trendy, but it’s been with you through thick and thin. It’s familiar, dependable, and safe.

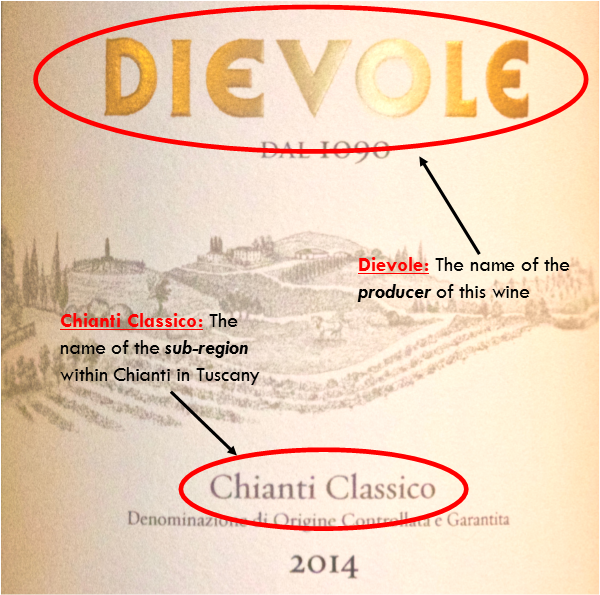

Continue readingThe “No Fear” Italian Wine Guide: Chianti

Chianti. Pinot Grigio. Barolo. Prosecco. We see these words pop up on every Italian restaurant’s wine list. They’re recognizable and familiar, and they’re meant to give us confidence when ordering a glass to go with our meal. But how are you supposed to decipher the long list of words that comes along with each option? Is Chianti the grape? Is this Prosecco sweet? Why is Barolo so expensive? If you don’t have a helpful sommelier on hand to guide you, ordering wine can be a daunting experience.

During the month of June, we’re focusing on taking the fear out of Italian wine. We’ll dig into the nuts and bolts of some commonly seen wines, explore some tried-and-true standbys and fail-proof food pairing options, and discover a few not-so-common alternatives if you’re looking to freshen up your wine drinking experience.

Chianti: What a Fiasco…

What to Expect: Chianti, the common term in all 3 wines listed above, is the name of the region the wine comes from. Located in the heart of Tuscany, the wines of Chianti primarily use the Sangiovese grape as the base for all their red wine production—by law, all Chianti must use a minimum of 75% Sangiovese. (It’s common to blend Sangiovese with a slew of other native Tuscan grapes—both red and white!—as well as some international grapes like Cab and Merlot.) The romantically rustic vision that many people have of Chianti wines is of a squat, round bottle nestled in a wicker basket holder called a fiasco (that later becomes a kitschy candle holder once the wine is gone).

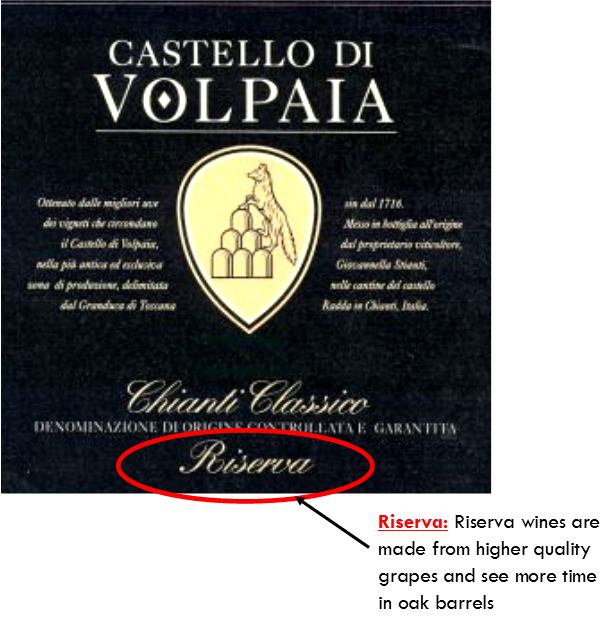

The Classics: Try out Selvapiana Chianti Rufina for a tried-and-true, classically-styled Chianti. Made from 100% Sangiovese, this is a perfect wine to understand exactly what the grape is all about–minimal oak aging, and no addition of other grapes. Just pure, unadulterated, gorgeous Sangiovese. If you want to know what a “step up” looks like in Chianti, revel in the Volpaia Chianti Classico Riserva. This sumptuous wine is made from a selection of only the top grapes harvested from Volpaia’s estate vineyards, and sees 2 years of oak aging before bottling. Everything is accentuated in Riserva wines: the color is deeper, the flavors are more intense, and the finish goes on for a mile.

Something Different: Chianti isn’t the only region to work with Sangiovese. You’ll find beautiful examples of it in Montalcino—a little town made famous for a particular strain of Sangiovese called Brunello. Coming only from select vineyards and aged for 2-4 years in barrel before release, Brunello di Montalcino commands premium prices and can be cellared for many years. The Caparo Brunello di Montalcino is a great place to start for understanding this side Sangiovese. But Montalcino also produces a more cost-effective wine, called Rosso di Montalcino, using the same special strain of Sangiovese, aged for less time in barrel and using younger vines sourced from bigger vineyards. The Ciacci Piccolomini Rosso di Montalcino is silky, gracious, and expressive on the palate, and stands out for its overall balance and harmony.

We’ve seen how well Sangiovese takes to being blended in Chianti wines, and that’s no less true in other regions as well! The term “Super Tuscan” came into popularity in the 1970s and 80s, when a few producers became disgruntled with the poor, thin, watered-down quality of wine that bore the government’s stamp of “high quality” Chianti. Taking matters into their own hands, they decided to forgo the government’s approval and began planting international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot to add to their Sangiovese, hoping to boost international opinion of Tuscan wine. Some of the most important wines to come of this experiment are well-known today, including Sassicaia, Ornellaia, and Tignanello. While these exquisite wines come with hefty price tags, there are a number of other “Super Tuscan”-styled wines at fantastic everyday prices. The ColleMassari “Rigoleto” Rosso is a fantastic example of a well-produced, organic blend using indigenous Tuscan varietals, and the Corzanello Toscana Rosso will show you how beautifully Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot can play with Sangiovese.

Perfect Pairings: Sangiovese has high natural acidity, a medium/medium-full body, and ripe, juicy red fruit notes. Sometimes they’ll have hints of savory, rustic herbal notes as well. Because of these characteristics, Chiantis are a fantastic match for tomato-based sauces. The acidity of the wine matches the acidity of the tomatoes—truly a perfect match! Chiantis find their way onto most restaurant wine lists because of the beautiful versatility they have in pairing with almost every Italian dish.

Try the Selvapiana Chianti Rufina with a hearty cheese like Wilde Weide Gouda. This pairing works because of the wine’s ripe, juicy red fruits, medium-full weight, and cleansing acidity–all of which balance out the cheese’s dense, fudgy, and slightly sweet notes. There’s some beautiful dried herbal notes in the Chianti, too, that parallel the gentle savory element in the cheese. What a Gouda pairing!