by Hailey

More so than almost anywhere else in the world, Italian wines are hard to understand. With over 355 grape varieties grown in the country, and some of the oldest wine regions in the world, it doesn’t take long to become overwhelmed with information. Yet when we think of Italian wine, Piedmont is one of the first words to come to mind.

The region holds a special place in Italian history as having played a leading role in the Italian unification process throughout the 18th century, as well as being the origin of the Italian Industrial Revolution that began at the tail end of the 1800s. It’s also one of the most well-known and renowned regions within Italy: not only does it hold vinous supremacy thanks to its vast number of fine and prestigious wines (a whopping 17 DOCGs and 42 DOCs), but also in its diversity and quantity of wines produced. Nebbiolo takes the crown here, at least in the number of high-quality wines produced – but wines made from this grape vary quite significantly throughout Piedmont.

The word Piedmont roughly translates to “foot of the mountain,” a nod to the topography of the region. It’s surrounded on all three sides by mountains: the Alps form the boundary with France on the West, and Switzerland and Vallee d’Aosta to the North; in the Southern part of the region, the Ligurian and Maritime Alps separate Piedmont from France and the Ligurian region within Italy. All of these mountains and hills make up a series three concentric rings (predominantly on the Western side of the region, with the Po Valley nestled in the East), and these mountains and hills are not only a defining characteristic of Piedmont itself, but also play a key role in which grapes are grown where, and how wines from each area of Piedmont present themselves in our glass. It’s the middle band, though, where most vines live. Planted between 500 – 1300 feet in elevation with sun exposure coming in all directions, it’s kind of like heaven on earth for Piedmont’s grapes, with each variety planted in the precise spots in the hills that will suit it best. The last, and most inner band, is the plain, which you can find along the Eastern side of Piedmont. Here, the principal crop is rice, not grapes, as the soil is too flat and fertile to suit quality vine growth.

Okay, here’s where things start to get more convoluted… Piedmont is organized into four major sub-regions, and within these subregions are clusters of hills. The most important in relation to Nebbiolo are the Monferrato hills, the Langhe hills, the Roero hills, and the Novara and Vercelli hills. To make things even more confusing, the hills are further divided into provinces, which are divided into districts and DOC(G)s.

The most Northerly of these provinces are the Navara and Vercelli Hills. Here, Nebbiolo goes by a different name: Spanna. The climate is milder, thanks to Lake Maggiore’s and Lake Orta’s moderating influences, and cool air from the alps swoops down to create super austere, high acid wines, while a wide diurnal range allows grapes to fully ripen. In relation to Nebbiolo, there’s two DOCGs to look out for from Northern Piedmont: Gattinara and Ghemme.

Gattinara and Ghemme are the two most Northerly DOCG’s for Nebbiolo, and the former boasts incredible natural grape growing conditions. The combination of perfect sun exposure, ideal altitudes, and soil mix create deliciously bright and aromatic wines, and thanks to these conditions, Nebbiolo (a very finicky grape!) does well here. Gattinara wines contain a higher percentage of Nebbiolo, a minimum of 90% with the other 10% of the blend being either Vespolina or Uva Rara. The combo of full tannins and high acid means that these babies are a bit crunchy and can take a while to mature. They’re full of all of the classic Nebbiolo notes of tart cherry, strawberry, tar, spice and violet, and are incredibly bright and a bit lighter in color than Piedmonts from more southerly areas of Piedmont, with a lighter body and slightly lower alcohol levels as well.

The Langhe and Roero hills, within the subregion of Alba, are found in the Southern part of Piedmont. This is where the bulk of France 44’s Piedmont section hails from, so if you frequently scan those shelves these words are probably ringing a bell for you. Besides wine, this part of Piedmont is also well regarded for hazlenuts, white truffles, and chocolate (this is where Nutella was invented!). The Ligurian Sea flanks the Southern part of Piedmont, so the conditions aren’t as brutal here and as a result the wines are much more consistent from year to year, with a fuller body and more alcohol than the wines of Northern Piedmont. Temperatures swing quite a bit between day and night in Alba, meaning the Nebbiolos of these parts are able to retain their signature acidity and are especially aromatic with notes of rose petal and violet bursting from the glass.

Within the Langhe Hills are the two appellations that are most closely associated with Piedmont: Barolo and Barbaresco. The winemaking philosophy of these regions is often compared to that of Burgundy: these are single varietal wines, with huge importance placed on the village origin of each wine. Most of the time, they are single-vineyard wines that are estate bottled. Vineyards are divided into tiny parcels, and these itty bitty lots of land are generally owned by multiple growers. For all of these parallels, Burgundy wine is nothing like that of Barolo or Barbaresco in character.

Barolo is known and loved for big, brooding power, but it actually wasn’t until the 1850’s that Paolo Francesco Staglieno created a dry style of Barolo. Prior to this, the area was known for sweet wines. As the drier style became more commonplace, they established themselves as the favorites of aristocrats throughout the area, earning the nickname “king of wines and wine of kings.” These wines do vary from bottle to bottle, though, and it’s mainly due to the type of soil they’re grown on (younger and more fertile Tartonian soils of Western Barolo, producing highly aromatic, elegant, fruitier, and more immediately drinkable wine; or the older, poorer Serravallian soils of the East, which produce way more powerful, robust, structured wines) or the style they’re made in (modern, with more fruity characters and more noticeable oak usage; or traditional, with more austerity and neutral, Slavonian oak usage). The Fantino family’s 2013 Barolo Bussia Cascina Dardi is a great example of a Barolo with both power and fruit, with hints of tobacco, leather, and a distinct richness added into the mix. Decant it and it’ll wow you with a surprisingly medium body and beautifully integrated tannins, or let it rest in your cellar and let the flavors morph more into dried fig, dried rose and violet, nutmeg, leather, game and meat.

Like Barolo, Barbaresco wines are 100% Nebbiolo. Elevation is lower here, and the Tanaro River is also closer, so the climate is a bit warmer than Barolo and grapes ripen fully with more ease and consistency. Beyond that, the terrain itself is more homogenous, so wines from commune to commune don’t vary as significantly as in Barolo. While both Barolo and Barbaresco are full of power and have lots of ageing potential, Barbaresco tends to be just a touch lighter, less austere, and more immediately approachable than many Barolos. If you’re looking for something immediately drinkable that still has some persuasive tannic body, Barbaresco is a great direction to go. The 2018 Luigi Giordano Barbaresco ‘Cavanna’ in particular is a staff favorite, so if we haven’t tried to sell you on it yet, you ought to give it a try! This is another one that you could drink now or cellar for half a decade or so, but drink it now and you’ll find a deliciously herbaceous dried sage quality alongside crushed red flowers and spicy, tart red fruit.

Nebbiolo d’Alba DOC wines are also varietal wines, pulling from over 30 communes on either side of the Tanaro River, excluding Barolo and Barbaresco. They’re full of wild strawberry, floral aromatics, and a bit of tar or bitter earth, but think of these are the baby sibling to Barolo and Barbaresco. These are lighter, less austere, and much less structured versions of Nebbiolo — perfect for you to get your Nebbiolo fix without breaking the bank too badly. Try the 2018 Bruno Giacosa Nebbiolo d’Alba and you’ll find an elegant, subtle wine with surprisingly fine tannins and notes of fresh black currant, raspberry, and cranberry.

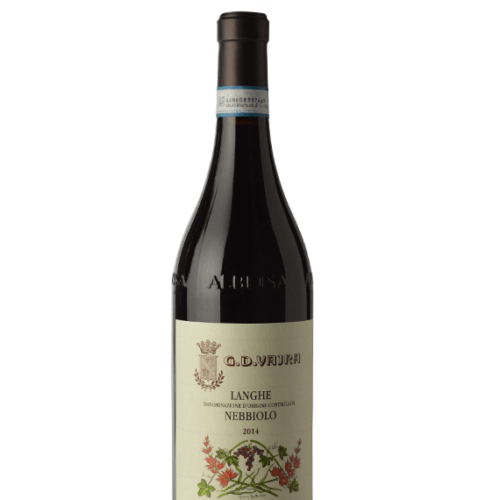

Last but certainly not least, the Langhe Nebbiolo DOC is used by Barbaresco and Barolo producers looking to release more approachable expressions of Nebbiolo, with less restrictive rules than would be required in their respective DOCGs. The DOC requires only 85% of the stated varietal to be included in the bottle, so there’s more versatility in blending, with less ageing in oak and bottle. These are some of the most budget friendly bottlings of Nebbiolo, and are great for everyday drinking! My go-to weeknight Nebbiolo is the 2019 Vajra Langhe Nebbiolo — it shows the perfume and aromatics that I love so much about this grape, and while it’s easy-drinking and definitely a fruitier style of Nebbiolo, it still has a decent amount of complexity. Black currant, wild mountain berry, lavender and rose petal are the shining notes here, with hints of blood orange and macerating strawberry on the finish.

Drink on, friends!

by Tashi

by Tashi

Playing for the Jews, it’s Sam Weisberg — wine and spirits specialist, Slivovitz enthusiast, and former theater kid who definitely loved Passover the most out of all of the other holidays because of all the singing he got to do at the dinner table.

Playing for the Jews, it’s Sam Weisberg — wine and spirits specialist, Slivovitz enthusiast, and former theater kid who definitely loved Passover the most out of all of the other holidays because of all the singing he got to do at the dinner table. On Christ’s team, we’ve got Josh Timmerman — wine specialist, social media mogul, fan of cocktails with less than three ingredients, and that guy from church who built his own deck and always seems really friendly but you can never remember his name.

On Christ’s team, we’ve got Josh Timmerman — wine specialist, social media mogul, fan of cocktails with less than three ingredients, and that guy from church who built his own deck and always seems really friendly but you can never remember his name.

, but this is splitting hairs. What’s important is that this Mexican sugarcane distillate (don’t censor me, rum gods) has a hard-to-pin-down style that almost tastes like a tequila-rum hybrid. The raw material here is a mix of both fresh sugarcane juice and molasses, with the former contributing fruity and grassy aromas to the aroma. Fiery, with some definite burn on the first sip, the palate eventually mellows into a drying, vegetal finish that tastes a lot like a tequila or non-smoky Mezcal. This would be killer in a very un-traditional Margarita.

, but this is splitting hairs. What’s important is that this Mexican sugarcane distillate (don’t censor me, rum gods) has a hard-to-pin-down style that almost tastes like a tequila-rum hybrid. The raw material here is a mix of both fresh sugarcane juice and molasses, with the former contributing fruity and grassy aromas to the aroma. Fiery, with some definite burn on the first sip, the palate eventually mellows into a drying, vegetal finish that tastes a lot like a tequila or non-smoky Mezcal. This would be killer in a very un-traditional Margarita.

Hamilton ‘Beachbum Berry’s Zombie Blend’ Rum | Ed Hamilton is a Minor God in the world of rum, having leveraged his travels around the Caribbean into an ever-growing line of rums which he meticulously sources from distilleries around the region. His rums have garnered the love of bartenders across the country, to the point where he often makes custom blends for specific bars that want a particular rum style for a particular cocktail. This is one such innovation, a blend of three different rums that was expressly made for bartenders looking to re-create Beachbum Berry’s (a Major God in tiki cocktails) Zombie recipe. It works for that recipe beautifully, but this also subs in anywhere you might need a rich, full-bodied dark rum for mixing—it’s unctuous and smooth, full of spice, caramelized banana, and roasted toffee notes.

Hamilton ‘Beachbum Berry’s Zombie Blend’ Rum | Ed Hamilton is a Minor God in the world of rum, having leveraged his travels around the Caribbean into an ever-growing line of rums which he meticulously sources from distilleries around the region. His rums have garnered the love of bartenders across the country, to the point where he often makes custom blends for specific bars that want a particular rum style for a particular cocktail. This is one such innovation, a blend of three different rums that was expressly made for bartenders looking to re-create Beachbum Berry’s (a Major God in tiki cocktails) Zombie recipe. It works for that recipe beautifully, but this also subs in anywhere you might need a rich, full-bodied dark rum for mixing—it’s unctuous and smooth, full of spice, caramelized banana, and roasted toffee notes.

CUATRO COPAS EXTRA AÑEJO TEQUILA I $99.99 I An incredibly complex and smooth Extra Añejo Tequila with notes of vanilla, caramel and citrus.

CUATRO COPAS EXTRA AÑEJO TEQUILA I $99.99 I An incredibly complex and smooth Extra Añejo Tequila with notes of vanilla, caramel and citrus.  PLANTATION XAYMACA RUM I $24.99 I With Xaymaca Special Dry, Plantation revives the quintessential Jamaican-style, 100% pot still rums of the 19th century with an expression of intense flavors that reveal the traditional, legendary Rum Funk: aromas and flavors of black banana and flambéed pineapple.

PLANTATION XAYMACA RUM I $24.99 I With Xaymaca Special Dry, Plantation revives the quintessential Jamaican-style, 100% pot still rums of the 19th century with an expression of intense flavors that reveal the traditional, legendary Rum Funk: aromas and flavors of black banana and flambéed pineapple.  EL DORADO 12 YEAR RUM I $36.99 I

EL DORADO 12 YEAR RUM I $36.99 I

BOWMAN BROTHERS SMALL BATCH BOURBON I $32.99 I The Bowman Brothers Small Batch Bourbon is distilled three times using the finest corn, rye, and malted barley, producing distinct hints of vanilla, spice, and oak.

BOWMAN BROTHERS SMALL BATCH BOURBON I $32.99 I The Bowman Brothers Small Batch Bourbon is distilled three times using the finest corn, rye, and malted barley, producing distinct hints of vanilla, spice, and oak. Pick up a box of mulling spices, a three-bottle sampler pack of your favorite spirit, or a pre-wrapped Mystery Mini gift.

Pick up a box of mulling spices, a three-bottle sampler pack of your favorite spirit, or a pre-wrapped Mystery Mini gift.

FOSSIL POINT PINOT NOIR | $17.99 | Showcasing notes of ripe plum, black cherry, clove, and pomegranate, this Pinot offers a quality well above its price point. Fossil Point Pinot has concentrated flavors that will pair well with slow-cooked pork belly, roasted duck or miso-glazed Salmon.

FOSSIL POINT PINOT NOIR | $17.99 | Showcasing notes of ripe plum, black cherry, clove, and pomegranate, this Pinot offers a quality well above its price point. Fossil Point Pinot has concentrated flavors that will pair well with slow-cooked pork belly, roasted duck or miso-glazed Salmon. ST. AGRESTIS AMARO | $39.99 | Although it is not a wine, the St. Agrestis Amaro is the perfect after dinner drink to cap off your holiday party! It is one of our staff favorites and is great for new Amaro drinkers and enthusiasts alike. Organic herbs, roots and citrus are macerated into a neutral spirit to produce this Brooklyn-made Amaro.

ST. AGRESTIS AMARO | $39.99 | Although it is not a wine, the St. Agrestis Amaro is the perfect after dinner drink to cap off your holiday party! It is one of our staff favorites and is great for new Amaro drinkers and enthusiasts alike. Organic herbs, roots and citrus are macerated into a neutral spirit to produce this Brooklyn-made Amaro.